http://www.ehowenespanol.com/ejercicios-pediatricos-balones-escoliosis-manera_93178/

|

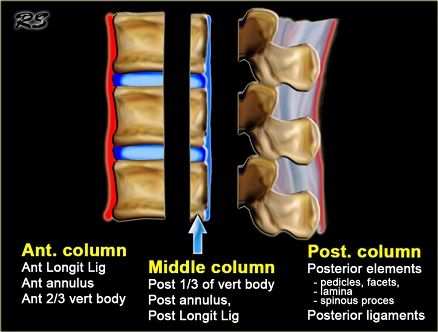

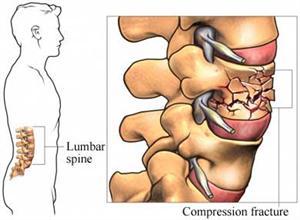

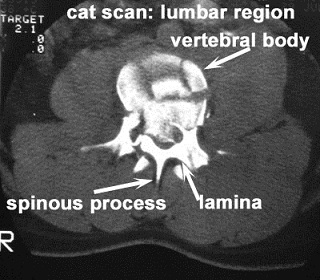

La escoliosis es un curvatura lateral anormal de la columna vertebral que usualmente tiene forma de S y a menudo se detecta durante la adolescencia o la infancia, cuando los huesos aún se están formando y creciendo. La escoliosis ocurre en, aproximadamente, un 2 por ciento de la población y la causa usualmente no se conoce. Aunque el verdadero tratamiento para esta enfermedad requiere de soportes para la espalda o cirugía para prevenir una progresión de la curvatura, la mayoría de la gente con escoliosis tiene curvaturas que no son lo suficientemente graves como para justificar ninguno de estos tratamientos. Pero los ejercicios para fortalecer los tejidos y músculos circundantes se recomiendan para mantener un buen estado físico y para mejorar la calidad de vida.

|

La escoliosis es un curvatura lateral anormal de la columna vertebral que usualmente tiene forma de S y a menudo se detecta durante la adolescencia o la infancia, cuando los huesos aún se están formando y creciendo. La escoliosis ocurre en, aproximadamente, un 2 por ciento de la población y la causa usualmente no se conoce. Aunque el verdadero tratamiento para esta enfermedad requiere de soportes para la espalda o cirugía para prevenir una progresión de la curvatura, la mayoría de la gente con escoliosis tiene curvaturas que no son lo suficientemente graves como para justificar ninguno de estos tratamientos. Pero los ejercicios para fortalecer los tejidos y músculos circundantes se recomiendan para mantener un buen estado físico y para mejorar la calidad de vida.

Tipos de ejercicios con balones

Los terapeutas físicos y otros profesionales de la salud usan los ejercicios terapéuticos con balones para reparar o fortalecer los músculos y los tejidos después de una lesión o una cirugía, o debido a los cuadros crónicos como la escoliosis o la artritis. Algunos de estos ejercicios pueden realizarse en casa después de tener entrenamiento suficiente con un terapeuta físico. Las rutinas con balones de ejercicio específicas para los músculos de la espalda que hay alrededor de la columna vertebral a menudo comienzan con extensiones de piernas, brazos y espalda. Balanceándose el estómago sobre un balón, una persona puede estirar las extremidades o hacer rodar el cuerpo a lo largo de la pelota para extender los músculos, usualmente se hacen de tres a cinco series de 10 repeticiones. A parte de los ejercicios de extensiones, las rutinas que se enfocan en los tríceps, el cuello y la espalda se realizan mientras la persona está sentada, y se balancea en un balón terapéutico. Algunos ejemplos de este entrenamiento ligero con pesos que opongan resistencia son las flexiones de brazo con la mancuerna en la espalda y movimientos de remado con un brazo, estos dos ejercicios tonifican el tríceps de tal manera que la tensión se quite de los músculos de la espalda cuando levantes o uses los músculos de los brazos, y las flexiones paralelas en posición sentada. Estas flexiones comienzan con una persona sentada sobre una pelota de ejercicios y doblándose al nivel de la cintura para pasar los brazos alrededor de los muslos y alcanzar unas pesas del suelo; este movimiento estira la espalda y permite que la persona tonifique los músculos de la espalda y los brazos al mismo tiempo. Utilizar un balón de ejercicios para balancearse de estas dos maneras principales ofrece resistencia y fortalecimiento muscular que puede reducir el dolor asociado con la curvatura progresiva de las vertebras en los adultos jóvenes con escoliosis.